What is Good Product Strategy? — Melissa Perri

This blog post critiques the common misconception of product strategy as merely a plan to build features. The author argues that a true product strategy is a system of goals and vision that aligns teams around desirable outcomes for both the business and its customers. This strategy emerges from experimentation towards a goal, where initiatives around features, products, and platforms are proven through testing and data. The post emphasizes the importance of shifting from output-driven metrics like feature development to outcome-driven metrics, focusing on the impact of those features on achieving business objectives.

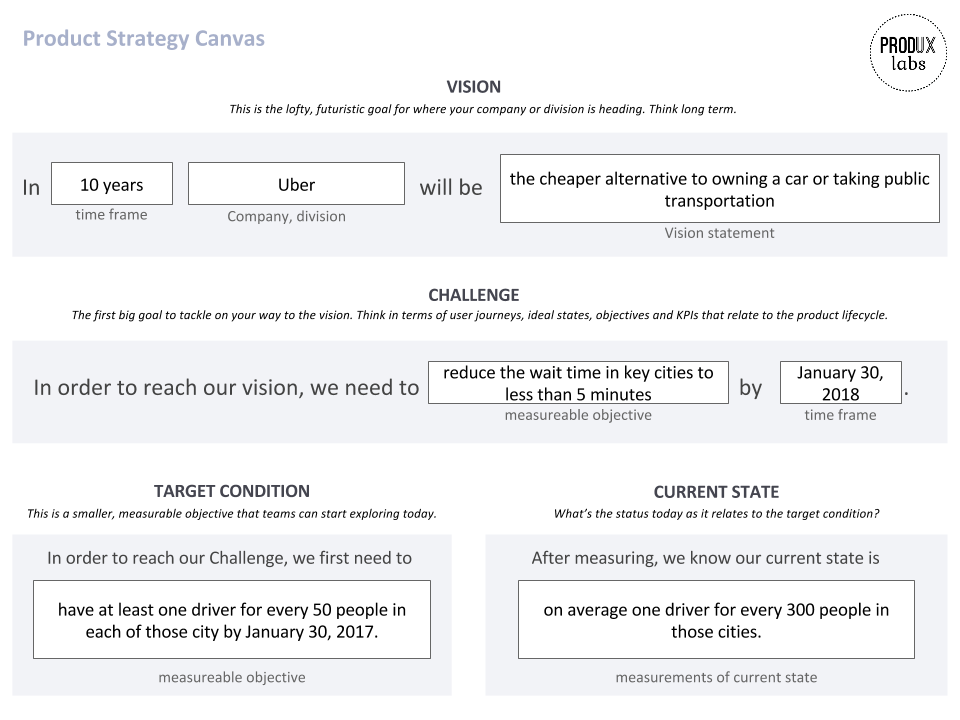

The author proposes a framework for product strategy that includes four key elements: Vision, Challenge, Target Condition, and Current State. This framework provides a structured approach for aligning teams towards achieving specific goals. The example of Uber illustrates how this framework can be applied to a real-world scenario, outlining the steps involved in identifying challenges, setting target conditions, and using experimentation to reach desired outcomes. The post concludes by advocating for a strategic approach to product roadmaps and communication with stakeholders, emphasizing the value of experimentation and continuous improvement in driving product success.

Note: This blog post is from 2016! My latest and improved thinking on Product Strategy can be found in my book Escaping the Build Trap and at our courses at Product Institute.

“What is your Product Strategy? YOU NEED A STRATEGY.” When I replay this scene in my head, I can hear the CTO very audibly yelling (slash pleading) with our product team. He was on edge. We had been experimenting towards a very concrete goal for two months, and had made a lot of progress. We had learned so much about what was preventing users from signing up on the site, and it was a lot clearer which direction in which we should be going. BUT we still had to test our ideas.

This didn’t sit well with the CTO because in reality he didn’t want a strategy, he wanted a plan. He wanted a list of what we were going to build, and when we were going to build it. He wanted to feel certain about what we were doing when we all came in tomorrow, so he could measure our progress based on how much we built. It’s not his fault though. This is the way we were taught to think about Product Strategy.

Most companies fall into the trap of thinking about Product Strategy as a plan to build certain features and capabilities. We often say our Product Strategy are things like:

-

“To create a platform that allows music producers to upload and share their music.”

-

“To create a backend system that will allow the sales team to manage their leads.”

-

“To create a front of the funnel website that markets to our target users and converts them.”

This isn’t a strategy, this is a plan. The problem is that when we treat a product strategy like a plan, it will almost always fail. Plans do not account for uncertainty or change. They give us a false sense of security. “If we just follow the plan, we’ll succeed!” Unfortunately, there is no guarantee of success here. (I wish there was, our jobs would be SO much easier!)

These product initiatives aren’t bad, they are just communicated at the wrong time and with the wrong intentions. When we lock ourselves into planning to build a set of features (ehem, Roadmaps), we rarely stop to question if those features are the right things to build to reach our goals. We stop focusing on the outcomes, and judge success of teams by outputs.

We need to have a plan but the plan shouldn’t be “build feature x.” Our plan should be to reach our business goals. We need to switch from thinking about Product Strategy as something that is dictated from top to bottom, and instead something that is uncovered as we learn what will help us achieve our objectives.

Product Strategy is a system of achievable goals and visions that work together to align the team around desirable outcomes for both the business and your customers.

Product Strategy emerges from experimentation towards a goal. Initiatives around features, products, and platforms are proven this way. Those KPIs, OKRs, and other metrics you are setting for your teams are part of the Product Strategy. But, they cannot create a successful strategy on their own.

We need a few core things for our Product Strategy to be successful:

Vision: The vision is your high level, ultimate view of where the company or business line is going. In large corporations, you want to narrow this to the business line or customer journey. In smaller companies, this will be your company and product’s overall vision. Think long term here, and keep it qualitative. This is a good chance to talk about competitors, how customers will see you, and ambitions for expansion.

Challenge: The challenge is the first Business goal you have to achieve on the way to your longer term vision. Which area of your customer journey or funnel needs to be optimized first? It’s communicated as a strategic objective that helps align and focus your team around a certain aspect of product development. This can be qualitative or quantitative. Try to keep these still in broad, high level terms. This one is the hardest for me to personally wrap my head around, but check out the example below for some clarity.

Target Condition: The target condition helps break down the Challenge. Challenges are made up of smaller problems you need to tackle along the way. These are set in terms of achievable, measurable metrics. When you set a target condition, your team shouldn’t know exactly how to reach it tomorrow. They should have a good idea of where to start looking through.

Current State: This is what the current reality is compared to the Target Condition. It should be measured and quantified before the work starts to achieve the first target condition.

Product Strategy Animation

These all contribute to something called “Unified Field Theory”, which is explained very nicely here by Bill Costantino and Mike Rother from Toyota Kata. When we are building products, we have a threshold of knowledge. We cannot start on Day 1 and exactly plan to reach our vision. There are too many unknowns and variables. Instead, we set goals along the way, then remove obstacles through experimentation until we reach our vision.

This is best explained through an example, so we’re going to use Uber. Let’s pretend you’re a Product Manager working on the platform that allows drivers to sign up.

Please note: I have no affiliation with Uber so this is a guess as how they might line up their strategy if they chose to use it. The vision is from a statement their CEO made in an interview. The rest I am improvising for the example.

Vision The CEO has stated that the company’s vision is to make Uber the cheap and efficient alternative to both owning a vehicle and taking public transportation. (He really said this in an interview, but everything after this is hypothetical).

Challenge So if we understand the Vision correctly, Uber wants people to use them as their sole source of transportation. They would first want to look at why other people are taking other transportation methods now instead of Uber. They may go out and interview people and find that in certain cities where Uber isn’t as popular, there is a very long wait time to get a car. They would compare this to other problems and determine how big it is in comparison. Let’s say it’s the biggest challenge at the moment. So the first goals they may want to tackle is decreasing the wait times in cities where it’s exceedingly long. Let’s say anything over 10 minutes on average is too long, and we want to decrease that down to 5 minutes or less because we’ve seen in cities with those wait times, people are 80% more likely to use Uber.

This is now our Challenge: Decrease wait times in cities where it is over 10 minutes to less than 5 minutes by January 30, 2018.

Target Condition As a Product Manager, you now want to figure out what is causing that long wait time. The problem in this case might be that there are not enough cars to serve that area. So our metric we care about now Acquisition of new drivers.

Our goal for our team should be measurable and achievable, something like: We want to onboard at least one driver for every 50 people in each city by January 30, 2017.

As the Product Manager responsible for the onboarding process for new drivers you would be tasked with contributing to that acquisition. You would first measure how many drivers per people in each city you currently have (Current Condition), then find the obstacles that are preventing new drivers from signing up today. Next, you experiment to remove each obstacle until you successfully hit your goal. The Product Kata explains how to do that.

So let’s step back and take a look at all that:

(You can download a blank copy of the Product Strategy canvas here.)

As a Product Manager, you don’t have control over all these numbers. The vision is set by CEOs, CPOs, Boards, and other C-Level Executives. The challenge is set by the next level of management (VP of Product for Each Journey or Business Line).

Direct Managers help their teams set effective Target Conditions. At the beginning these may need to be handed down from management. As teams get used to this way of working, the managers and team can work together to set them.

Once these four items are set and communicated, the team can start applying the Product Kata method to figure out how to reach the goals. It’s the Product Manager and their team’s responsibility to determine the user problems and other obstacles standing in the way of achieving that Target Condition. Then they experiment to solve them.

This aligns everyone around a strategic goal and vision. Every level of the portfolio has their objectives. Teams are held accountable for their progress towards the goal they are responsible for reaching.

Now you have probably looked at this and said “well this isn’t a product strategy, it’s a business strategy.” Yes, this does come off looking like a bunch of business objectives, but isn’t that why we built a product? To reach our business objectives? Product Management is the art of solving your customer’s problems to reach your business objectives. If you’re not doing both of those things, your product is just a fancy piece of code for show.

The next post will be on how to format your Product Roadmaps around these strategies, and how to communicate with stakeholders to encourage experimentation.